|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Subscribe to this newsletter at www.drmcdougall.com |

|

||||||

|

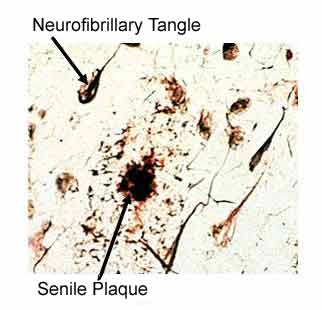

AD is a progressive disease that destroys the mind with forgetfulness in early stages, followed by the inability to communicate and provide self-care. On average, patients die within 8 years of the onset of the first symptoms, but the disease can linger as long as 20 years. The five drugs currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of AD patients (tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, and memantine), at most, improve symptoms, and none has been shown to slow the progression of AD. Therefore, it is imperative that no obstacle stand in the way of utilizing the knowledge we presently have to spare others the kind of suffering inflicted upon the Reagan family. While research into genetic causes and stem-cell treatments may be intriguing, they are currently, at best, in the distant realm of science fiction, and of no practical use for us here and now. Our attention should be focused on practical matters, such as our diet and avoidance of toxic substances, because this translates immediately into cost-free, highly-effective, non-toxic approaches for prevention and treatment of any disease. Plaques and Tangles – The Pathology of AD AD is characterized by the death of brain cells. The diagnosis is firmly established by seeing on microscopic examination two characteristic changes that follow years of repeated injury – and the resulting chronic inflammation. The main feature of AD is clumps of protein, called beta-amyloid deposits, which are commonly referred to as senile plaques. These deposits are found in the spaces between the brain cells. The senile plaques are so important for the diagnosis of AD that they are often referred to as pathognomonic lesions1 – this word means, if you see the pathology, then you can name the disease – in other words, finding a significant numbers of these senile plaques on microscopic examination establishes that the patient had AD.

Injury results in damage within the brain cells, too. Tiny (micro) tubules make up the structure of the inside of the brain cells, and serve to transport substances into and out of the cells – when damaged they clump together forming filamentous snarls, known as neurofibrillary tangles. Thus, our focus of attention needs to be upon the scientific research that identifies the sources of injury that result in these two characteristic lesions of AD (senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles). The Meat of the (Brain) Matter Chronic injury to arteries results in atherosclerosis which is characterized by lesions also called plaques. Many of the tissue changes found on examination are similar to both AD and atherosclerosis.2,3 In the case of atherosclerosis, which leads to coronary heart disease (CHD), scientists have firmly established that the rich American diet – high in cholesterol and fat, and lacking in healthful ingredients found naturally in plant foods – plays a pivotal, causal role.

Toxic Damage of Brain Tissues by Aluminum Aluminum is a recognized neurotoxin that is believed to be at the root cause of AD. Aluminum becomes more toxic when combined with a high-cholesterol diet – they work together by means that have yet to be fully determined to create the senile plaques and ultimately the mental deterioration known as AD.22 However, there are at least two recognized synergistic ways that these factors contribute to brain damage: First, an acid-forming diet – one high in meat, poultry, eggs, and cheese – leads to increased serum and brain concentrations of aluminum.23 Second, aluminum enhances inflammation. The immune enhancing properties of aluminum were discovered after immunization with diphtheria and tetanus vaccines in studies performed in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, and aluminum is used today to enhance the effectiveness the inflammatory response of most vaccines given to adults and children. In the brain, aluminum enhances the inflammation that may result from the formation of senile plaques driven by cholesterol build up. Just as important, aluminum may also be a source of initial injury – this metal is a known toxin to the nervous system – that starts the disease processes, leading to brain cell death, senile plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles.24 The Evidence That Aluminum Causes AD Is Compelling25 Aluminum was found to be toxic to the nervous system of animals over 100 years ago. Injecting aluminum into the brains of sheep was reported in 1965 to result in changes in the brain that showed a “striking resemblance” to AD in people. In 1973, brains of AD patients were found to contain more aluminum than people dying without this disease. About the same time, kidney patients on dialysis were found to suffer, sometimes fatal, brain damage (encephalopathy) from aluminum in their antacids (these antacids are used to bind phosphates in their intestines). More than 100 toxic actions of aluminum have been identified and many are damaging to the human brain.

How to Minimize Aluminum Exposure: Aluminum Is in Our Foods38 Aluminum is the most abundant metal in the earth’s crust and the third most abundant element, behind oxygen and silicon. Aluminum is present in our water, foods, medications, and air. The healthy human body has effective barriers, such as the skin, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract, against aluminum. Aluminum is not a nutrient – in other words, the body has no need for this metal – and avoidance has no negative consequences. All foods naturally contain aluminum, but some, such as tea, are particularly high in this metal. Fortunately, most of the aluminum in natural plant foods is bound with other substances, such as silicon, which prevents absorption of the aluminum into the body. The harmful (unbound, more easily absorbable) forms of aluminum enter our foods as additives, such as a leavening agent, emulsifier, acidifying agent, anti-caking agent, or coloring. Cooking, packaging and handling foods in aluminum containers increase the amount of this toxic metal in foods.

The cans used for carbonated and non-carbonated beverages, like colas and fruit drinks, leak significant amounts of aluminum into the beverage.39 Most canned-food containers, however, are made of steel, not aluminum. The use of aluminum skillets, pressure cookers, pans, pots, coffee makers, dinner trays, wraps and foils all add aluminum to foods. Long cooking in an acidic environment, and using new pots and pans, further increases aluminum leaching into the food. For example, tomato products provide an acidic environment during cooking – using an aluminum pot to simmer tomato sauce increases the aluminum concentration by 570 times.38

Avoid Medications Containing Aluminum Look at the labels of your over-the-counter medications. You will find aluminum as an active ingredient in many antacids. People may be consuming 840 to 5000 mg of aluminum a day from this source.38 Pain killers (analgesics) often have aluminum as an inactive ingredient (130 to 730 mg/day can be consumed).38 Some calcium supplements contain small amounts of aluminum. Also look up your prescription medications on the Internet or in a PDR (Physician’s Desk Reference), and you will often find aluminum used as an inactive ingredient. Taking Citracal© (calcium citrate antacids) increases aluminum absorption into the body by 8 to 11 times over the absorption that would occur when aluminum is present in the intestine without citrate.40-42 Many liquid and wafer antacids do not contain citrate, such as TUMS with calcium carbonate. In the United States, aluminum potassium sulfate is the only approved substance used to enhance the immune response and approved for use in vaccines. Some researchers consider this a serious matter and suspect that the amounts given during routine vaccination can cause an ongoing inflammatory response in the brain.43 Aluminum from the Air In AD there has been a tendency for some of the greatest accumulation of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles to occur in the olfactory lobes of the brain.44 This is the only portion of the brain that has direct exposure to the outside environment, through the nose. Here the smell-sensitive nervous tissues have the capacity to pick up and transmit substances like aluminum directly into the brain.44,45 In the past, most of the airborne aluminum came from industrial sources. There is now a new and common source of airborne aluminum and that is from antiperspirants. Every morning people are spraying past their armpits right into their faces with these products. One study found a 60% greater risk of AD with use of antiperspirants, and a trend toward a higher risk with increasing frequency of use.46 All antiperspirants contain aluminum chloride – which stops the sweating. Plain deodorants do not contain this aluminum ingredient. McDougall’s Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease Fortunately, the recommendations for AD are the same ones that I would offer for the prevention and treatment for most of the other common diseases which plague people who follow the rich Western diet: Consume a low-fat, no-cholesterol, plant-based diet and avoid toxic substances -- the focus in this case is aluminum, but iron may also be important. There is absolutely no reason to delay following this advice – the benefits are documented for many diseases and for health in general. Your goals should be similar to the ones you already know for heart disease. For example, you should strive for a blood total cholesterol level below 150 mg/dl. You accomplish this, first and foremost, by following a no-cholesterol, low-fat diet based on plant foods (The McDougall Diet). Depending upon the degree of impending risk for future trouble (for example heart disease, stroke, or AD) you may decide to add cholesterol-lowering medications in order to accomplish this goal. (See my September 2002 Newsletter article, “Cholesterol - When and How to Treat.”) Someone suffering with AD should be even more aggressive with treating cholesterol and removing toxic aluminum from the body. In this case I would be more inclined to prescribe statin medications, with a goal of achieving a cholesterol level below 150 mg/dl. (See my June 2003 Newsletter article, “Cleaning out Your Arteries,” for a relevant discussion on treating artery disease and a guide to AD treatment.) There is an argument that the kind of medication matters – statins which do not easily cross the blood-brain barrier (like Lipitor does not easily cross) should be used.47 Next, for someone with AD I would administer desferrioxamine, 125 mg intramuscularly twice daily for 5 days per week for months and maybe years, in order to remove aluminum and iron from the body.36,37 Although daily injections may seem painful, they do not approach the suffering from the progressive loss of mental function of AD. (By the way, desferrioxamine is a low-profit drug that cannot be patented and this is the reason you have not heard about this treatment. This all may change for drug treatments for AD when high profit statins are recommended, and advertised to patients and doctors.) So you see you are no more helpless with AD then you are with CHD (coronary heart disease). Your options are mostly limited by what you know. Since money drives information, too few people know about these simple, scientifically-based steps I have outlined to avoid the suffering of AD and other common diseases.

References: 1) Reilly JF, Games D, Rydel RE, Freedman S, Schenk D, Young WG, Morrison JH, Bloom FE. Amyloid deposition in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex: quantitative analysis of a transgenic mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Apr 15;100(8):4837-42. 2) Kalaria RN. Comparison between Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia: implications for treatment. Neurol Res. 2003 Sep;25(6):661-4. 3) Mucchiano GI, Haggqvist B, Sletten K, Westermark P. Apolipoprotein A-1-derived amyloid in atherosclerotic plaques of the human aorta. J Pathol. 2001 Feb;193(2):270-5. 4) Jorm AF,

Jolley D. The incidence of dementia: a meta-analysis. 5) White L, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Masaki KH, Abbott RD, Teng EL, Rodriguez BL, Blanchette PL, Havlik RJ, Wergowske G, Chiu D, Foley DJ, Murdaugh C, Curb JD. Prevalence of dementia in older Japanese-American men in Hawaii: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. JAMA. 1996 Sep 25;276(12):955-60. 6) Hendrie HC, Osuntokun BO, Hall KS, Ogunniyi AO, Hui SL, Unverzagt FW, Gureje O, Rodenberg CA, Baiyewu O, Musick BS. Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease and dementia in two communities: Nigerian Africans and African Americans. Am J Psychiatry. 1995 Oct;152(10):1485-92. 7) Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, Tangney CC, Bennett DA, Aggarwal N, Schneider J, Wilson RS. Dietary fats and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2003 Feb;60(2):194-200. 8) Kalmijn S, Feskens EJ, Launer LJ, Kromhout D. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, antioxidants, and cognitive function in very old men. Am J Epidemiol. 1997 Jan 1;145(1):33-41. 9) Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Shea S, Mayeux R.Caloric intake and the risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2002 Aug;59(8):1258-63. 10) Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Ruitenberg A, Van Swieten JC, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Breteler MM. Diet and risk of dementia: Does fat matter?: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2002 Dec 24;59(12):1915-21. 11) Notkola IL, Sulkava R, Pekkanen J, Erkinjuntti T, Ehnholm C, Kivinen P, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A. Serum total cholesterol, apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele, and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroepidemiology. 1998;17(1):14-20. 12) Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Laakso MP, Hanninen T, Hallikainen M, Alhainen K, Soininen H, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A. Midlife vascular risk factors and Alzheimer's disease in later life: longitudinal, population based study. BMJ. 2001 Jun 16;322(7300):1447-51. 13) Jarvik GP, Wijsman EM, Kukull WA, Schellenberg GD, Yu C, Larson EB. Interactions of apolipoprotein E genotype, total cholesterol level, age, and sex in prediction of Alzheimer's disease: a case-control study. Neurology. 1995 Jun;45(6):1092-6. 14) Kuo YM, Emmerling MR, Bisgaier CL, Essenburg AD, Lampert HC, Drumm D, Roher AE. Elevated low-density lipoprotein in Alzheimer's disease correlates with brain abeta 1-42 levels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998 Nov 27;252(3):711-5. 15) Hofman A, Ott A, Breteler MM, Bots ML, Slooter AJ, van Harskamp F, van Duijn CN, Van Broeckhoven C, Grobbee DE. Atherosclerosis, apolipoprotein E, and prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in the Rotterdam Study. Lancet. 1997 Jan 18;349(9046):151-4. 16) Jick H, Zornberg GL, Jick SS, Seshadri S, Drachman DA. Statins and the risk of dementia. Lancet. 2000 Nov 11;356(9242):1627-31. 17) Wolozin B, Kellman W, Ruosseau P, Celesia GG, Siegel G.Decreased prevalence of Alzheimer disease associated with 3-hydroxy-3-methyglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Arch Neurol. 2000 Oct;57(10):1439-43. 18) Fassbender K, Simons M, Bergmann C, Stroick M, Lutjohann D, Keller P, Runz H, Kuhl S, Bertsch T, von Bergmann K, Hennerici M, Beyreuther K, Hartmann T.Simvastatin strongly reduces levels of Alzheimer's disease beta -amyloid peptides Abeta 42 and Abeta 40 in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 May 8;98(10):5856-61. 19) Friedhoff LT, Cullen EI, Geoghagen NS, Buxbaum JD. Treatment with controlled-release lovastatin decreases serum concentrations of human beta-amyloid (A beta) peptide. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001 Jun;4(2):127-30. 20) Foley DJ, White LR. Dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of Alzheimer disease: food for thought. JAMA. 2002 Jun 26;287(24):3261-3. 21) Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Ruitenberg A, van Swieten JC, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Breteler MM. Engelhart Dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002 Jun 26;287(24):3223-9. 22) Sparks DL, Lochhead J, Horstman D, Wagoner T, Martin T. Water quality has a pronounced effect on cholesterol-induced accumulation of Alzheimer amyloid beta (Abeta) in rabbit brain. J Alzheimers Dis. 2002 Dec;4(6):523-9. 23) Grant WB, Campbell A, Itzhaki RF, Savory J. The significance of environmental factors in the etiology of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2002 Jun;4(3):179-89. 24) Campbell A, Yang EY, Tsai-Turton M, Bondy SC. Pro-inflammatory effects of aluminum in human glioblastoma cells. Brain Res. 2002 Apr 12;933(1):60-5. 25) Savory J, Garruto RM. Aluminum, tau protein, and Alzheimer's disease: an important link? Nutrition. 1998 Mar;14(3):313-4. 26) Crapper DR, Krishnan SS, De Boni U, Tomko GJ. Aluminum: a possible neurotoxic agent in Alzheimer's disease. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1975;100:154-6. 27) Candy JM, Oakley AE, Klinowski J, Carpenter TA, Perry RH, Atack JR, Perry EK, Blessed G, Fairbairn A, Edwardson JA. Aluminosilicates and senile plaque formation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1986 Feb 15;1(8477):354-7. 28) Campbell A. The potential role of aluminum in Alzheimer's disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17 Suppl 2:17-20. 29) Zatta P, Lucchini R, van Rensburg SJ, Taylor A. The role of metals in neurodegenerative processes: aluminum, manganese, and zinc. Brain Res Bull. 2003 Nov 15;62(1):15-28. 30) Shin RW, Kruck TP, Murayama H, Kitamoto T. A novel trivalent cation chelator Feralex dissociates binding of aluminum and iron associated with hyperphosphorylated tau of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2003 Jan 24;961(1):139-46. 31) Kawahara M, Kato M, Kuroda Y. Effects of aluminum on the neurotoxicity of primary cultured neurons and on the aggregation of beta-amyloid protein. Brain Res Bull. 2001 May 15;55(2):211-7. 32) Flaten TP.. Aluminum as a risk factor in Alzheimer's disease, with emphasis on drinking water. Brain Res Bull. 2001 May 15;55(2):187-96. 33) Taylor GA, Ferrier IN, McLoughlin IJ, Fairbairn AF, McKeith IG, Lett D, Edwardson JA. Gastrointestinal absorption of aluminum in Alzheimer's disease: response to aluminum citrate. Age Ageing. 1992 Mar;21(2):81-90. 34) Moore PB, Day JP, Taylor GA, Ferrier IN, Fifield LK, Edwardson JA. Absorption of aluminum-26 in Alzheimer's disease, measured using accelerator mass spectrometry. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000 Mar-Apr;11(2):66-9. 35) Rogers MA, Simon DG. A preliminary study of dietary aluminum intake and risk of Alzheimer's disease. Age Ageing. 1999 Mar;28(2):205-9. 36) McLachlan DR, Dalton AJ, Kruck TP, Bell MY, Smith WL, Kalow W, Andrews DF. Intramuscular desferrioxamine in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1991 Jun 1;337(8753):1304-8. 37) McLachlan

DR, Smith WL, Kruck TP. Desferrioxamine and Alzheimer's disease: video

home behavior assessment of clinical course and measures of brain

aluminum. 38) Soni MG, White SM, Flamm WG, Burdock GA. Safety evaluation of dietary aluminum. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2001 Feb;33(1):66-79. 39) Duggan JM, Dickeson JE, Tynan PF, Houghton A, Flynn JE. Aluminum beverage cans as a dietary source of aluminum. Med J Aust. 1992 May 4;156(9):604-5. 40) Nolan CR, DeGoes JJ, Alfrey AC. Aluminum and lead absorption from dietary sources in women ingesting calcium citrate. South Med J. 1994 Sep;87(9):894-8. 41) Coburn JW, Mischel MG, Goodman WG, Salusky IB. Calcium citrate markedly enhances aluminum absorption from aluminum hydroxide. Am J Kidney Dis. 1991 Jun;17(6):708-11. 42) Walker JA, Sherman RA, Cody RP. The effect of oral bases on enteral aluminum absorption. Arch Intern Med. 1990 Oct;150(10):2037-9. 43) Campbell A, Becaria A, Lahiri DK, Sharman K, Bondy SC. Chronic exposure to aluminum in drinking water increases inflammatory parameters selectively in the brain. J Neurosci Res. 2004 Feb 15;75(4):565-72. 44) Perl DP,

Good PF. Aluminum, Alzheimer's disease, and the olfactory system. 45) Christen-Zaech S, Kraftsik R, Pillevuit O, Kiraly M, Martins R, Khalili K, Miklossy J. Early olfactory involvement in Alzheimer's disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 2003 Feb;30(1):20-5. 46) Graves AB,

White E, Koepsell TD, Reifler BV, van Belle G, Larson EB. The

association between aluminum-containing products and Alzheimer's

disease. 47) Sparks DL, Connor DJ, Browne PJ, Lopez JE, Sabbagh MN. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and why it would be ill-advise to use one that crosses the blood-brain barrier. J Nutr Health Aging. 2002;6(5):324-31. 48) Puglielli L, Tanzi RE, Kovacs DM. Alzheimer's disease: the cholesterol connection. Nat Neurosci. 2003 Apr;6(4):345-51. 49) Ewbank

DC. Deaths attributable to Alzheimer's disease in the United States. 50) CDC.

Mortality Trends for

Alzheimer's Disease, 1979-91 51) No Authors. From the Centers for Disease Control. Mortality from Alzheimer disease--United States, 1979-1987. JAMA. 1991 Jan 16;265(3):313,317. |

|||||||

|

|||||||