Protein OverloadMuscle, vitality,

strength, power, energy, vigor, aggressiveness, and liveliness are words

that come to mind when people think of the benefits of protein in their

diet. The truth is quite the opposite. Bone loss,

osteoporisis, kidney damage, kidney

stones, immune dysfunction, arthritis, cancer promotion, low-energy, and overall poor health are

the real consequences from overemphasizing protein. Protein serves as raw

material to build tissues. Without sufficient protein from your diet,

your body would be in trouble – but, aside from starvation, this never

happens. Yes, a little protein is good, but more is not better. Protein

consumed beyond our needs is a health hazard as devastating as excess

dietary fat and cholesterol. Unfortunately, almost everyone on the

typical Western diet is overburdened with protein to the point of physical

collapse. The public has almost no awareness of problems of protein

overload, but scientists have known about the damaging effects of excess

protein for more than a century.

In his book, Physiology Economy in

Nutrition, Russell Henry Chittenden, former

President of the American Physiological Society (APS) and Professor of

Physiological Chemistry at Yale, wrote in 1905, “Proteid (protein)

decomposition products are a constant menace to the well-being of the

body; any quantity of proteid or albuminous food beyond the real

requirements of the body may prove distinctly injurious…Further, it

requires no imagination to understand the constant strain upon the liver

and kidneys, to say nothing of the possible influence upon the central and

peripheral parts of the nervous system, by these nitrogenous waste

products which the body ordinarily gets rid of as speedily as possible.”1

What are

Your Construction (Protein) Needs?

Protein from

your diet is required to build new cells, synthesize hormones, and repair

damaged and worn out tissues. So how much do you need?

The protein lost from the body each day

from shedding skin, sloughing intestine, and other miscellaneous losses is

about 3 grams per day (0.05 grams/Kg).3 Add to this loss other

physiological requirements, such as growth and repairs. The final tally,

based on solid scientific research, is: your total daily need

for protein is about 20 to 30 grams.4,5 Plant

proteins easily meet these needs.6

So what are people consuming? Those

living in many rural Asian societies consume about 40 to 60 grams from their

diet of starch (mostly rice) with vegetables.6 On the Western diet,

typical food choices centered around meat and dairy products, “a

well-balanced diet,” provides about 100 to 160 grams of protein a day. A

traditional Eskimo, eating marine animals, or someone on the Atkins diet,

from various kinds of meat and dairy, might be consuming 200 to

400 grams a day.7 Notice that there

can be a 10-fold (1000%) difference from our basic requirements and the

amount some

people consume. The resilience of the human body allows for survival

under conditions of incredible over-consumption.

Once the body’s needs are

met, then the excess must be removed. The liver converts the excess

protein into urea and other nitrogen-containing breakdown products, which

are finally eliminated through the kidneys as part of the urine.

Excess Protein Burdens

the Kidneys and Liver

Processing all that excess dietary protein

– as much as 300 grams (10 ounces) a day –causes wear and tear on the

kidneys; and as a result, on average, 25% of kidney function is lost over

a lifetime (70 years) from consuming the Western diet.8,9 Fortunately, the

kidneys are built with large reserve capacity and the effects of losing

one-quarter of kidney function are of no consequence for otherwise healthy

people. However, people who

have already lost kidney function for other reasons – from an accident,

donation of a kidney, infection, diabetes, and hypertension – may suffer

life-threatening consequences from a diet no higher in protein than the

average American consumes.10,11

The time-honored fundamental treatment for

people with failing kidneys is a low-protein diet. End-stage kidney

failure, requiring dialysis, can usually be postponed or avoided by

patients fortunate enough to learn about the benefits of a low-protein

diet.10-13

People suffering with liver failure are also placed on diets low in

protein as fundamental therapy – short of a liver transplant, this is the most important therapy they

will receive. During the end stages of liver failure, patients will often

fall into a coma from the build-up of protein breakdown products (hepatic

coma). A change to a cost-free, very low-protein diet can cause these

dying people to awaken. Well planned, plant-food based diets are

particularly effective with both kidney and liver disease.14,15

Excess Protein Damages the Bones =

Osteoporosis

Worldwide, rates of hip fractures (and

kidney stones) increase with increasing animal protein consumption

(including dairy products). For example, people from the USA, Canada,

Norway, Sweden, Australia, and New Zealand have the highest rates of

osteoporosis. 15,16 The lowest rates are among people who eat

the fewest animal-derived foods (these people are also on lower calcium

diets) – like the people from rural Asia and rural Africa.15,16

Osteoporosis is caused by several

controllable factors; however, the most important one is the foods we

choose – especially the amount of animal protein and the foods high in

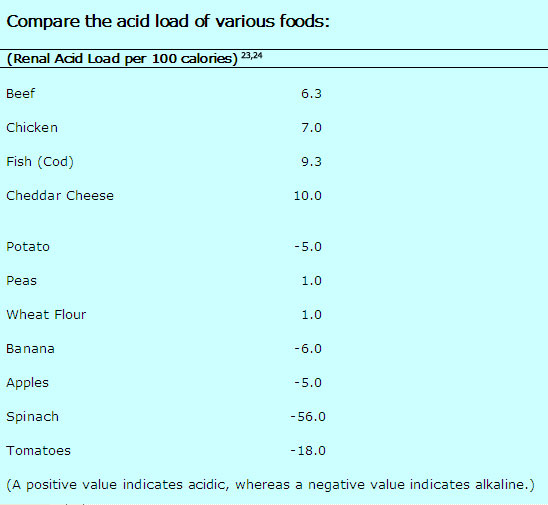

acid.17-19 The high acid foods are meat, poultry, fish,

seafood, and hard cheeses – parmesan cheese is the most acidic of all

foods commonly consumed.20 This acid must be neutralized

by the body.21 Carbonate, citrate and sodium are alkaline materials

released from the bones to neutralize the acids. Fruits and vegetables

are alkaline and as a result a diet high in these plant foods will

neutralize acid and preserve bones. The acidic condition of the body

caused by the Western diet also raises cortisol (steroid) levels. 22

Elevated cortisol causes severe chronic bone loss – just like giving

steroid medication for arthritis causes severe osteoporosis.

Consequence Two: Kidney Stones

Once materials are released from the solid bone, the

calcium and other bone substances move through the blood stream to the

kidneys where they are eliminated in the urine. In an effort to remove the

overabundance of waste protein, the flow of blood through the kidneys

(glomerular filtration rate) increases – the result: calcium is filtered

out of the body. Naturally, the kidneys attempt to return much of this

filtered calcium back to the body; unfortunately, the acid and

sulfur-containing amino acids from the animal foods thwart the body’s

attempts to conserve calcium. The final result is each 10 grams of

dietary protein in excess of our needs (30 grams daily) increases daily

urinary calcium loss by 16 mg. Another way of looking at the effects is:

doubling protein intake from our diet increases the loss of calcium in our

urine by 50%.25

Plant proteins (plant food-bases) do not have these calcium and

bone losing effects under normal living conditions.

Once this

bone material arrives in the collecting systems of the kidney it easily

precipitates into sold formations known as kidney stones.27

Over 90% of kidney stones found in people following a high-protein,

Western diet are formed primarily of bone-derived calcium. Following a

healthy diet is the best way to prevent kidney stones.28

Toxic Sulfur Distinguishes Animal Foods

The qualities of the

proteins we consume are as important as the quantities. One very

important distinction between animal and plant-derived protein is that animal

proteins contain very large amounts of the basic element sulfur.

This sulfur is found as two of the twenty primary amino acids,

methionine and cysteine. Derived from these two primary

sulfur-containing amino acids are several other sulfur-containing amino

acids – these are keto-methionine, cystine, homocysteine, cystathionine,

taurine, cysteic acid.

|

|

|

|

Methionine |

Valine |

The yellow sphere represents the element sulfur.

Even though

sulfur-containing amino acids are essential for our survival, an excess of

these amino acids beyond our needs places a critical burden upon our body

and detracts from our health in six important ways:

1) Amino acids, as

the name implies are acids; the sulfur-containing amino acids are the

strongest acids of all, they breakdown into powerful sulfuric acid.

Excess acid, as discussed above, is a primary cause of bone loss leading

to osteoporosis and kidney stone formation.29

2) Methionine is

metabolized into homocysteine – animal foods are the major source of the

amino acid, homocysteine, in people – the more meat in the diet, the

higher a person’s blood level of homocysteine. A diet high in fruits and

vegetables lowers the levels of this amino acid. Epidemiological and

clinical studies have proven homocysteine to be an independent risk factor

for heart attacks, strokes, closure of the arteries to the legs

(peripheral vascular disease), blood clots in the legs (venous

thrombosis), thinking problems (cognitive impairment), and even worse

mental troubles, like dementia, Alzheimer's disease, and depression.30

3) Sulfur feeds cancerous

tumors. Cancer cell metabolism is dependent upon methionine being in the

diet; whereas, normal cells can grow on a methionine-free diet (feeding

off of other sulfur-containing amino acids). This methionine-dependency

has been demonstrated for breast, lung, colon, kidney, melanoma, and brain

cancers.31,32 Increasing methionine in the diet of animals promotes the growth

of cancer.33

There is also evidence of

cancer promoting effects of methionine mediated through a powerful growth

stimulating hormone, called insulin-like growth factor - 1

(IGF-1).34 Meat and dairy products raise IGF-1 levels and promote the

growth of cancers of the breast, colon, prostate, and lung.35

4) Sulfur from sulfur-containing amino acids is known

to be toxic to the tissues of the intestine, and to have deleterious

effects on the human colon, even at low levels.36 The

consequence of a diet of high-methionine (animal) foods may be a

life-threatening inflammatory bowel disease, called ulcerative colitis.37-38

5) Sulfur restriction prolongs life.39 Almost seventy

years ago, restricting food consumption was found to prolong the life of

animals by changing the fundamental rate at which aging occurs.40

Restriction of methionine in the diet has also been shown to prolong the

life of experimental animals. By no coincidence, a diet based on plant

foods is inherently low in both calories and methionine – thus the easiest

and most effective means to a long and healthy life.

6) Possibly a stronger motivation to keep protein,

and especially methionine-rich animal protein, out of your diet is foul

smelling odors – halitosis, body odor, and noxious flatus – akin to the

smell of rotten eggs – are direct results of the sulfur (animal protein)

you eat.41,42

Do Not Waste Your Health Away

Animal foods, full of protein waste, promote poor health

and early death by accelerating the aging process and increasing the risk

of diseases, like heart disease, diabetes, and cancer, that in their own

right, cause premature death. From now on, think of the excess protein

you consume as garbage that must be disposed of in order to avoid toxic

waste accumulation. Obviously, the best action is to avoid the excess in

the first place and this is most easily accomplished by choosing a diet

based on starches, vegetables, and fruits. Within a few days of changing

to a healthy diet, most of the waste will be gone and the damaged

tissues will begin healing.

Unfortunately, you will find little support

for such an obvious, inexpensive, and scientifically-supported approach –

especially when the common masses of people worldwide are ignorant of the

truth – most are gobbling down as much protein as they can stuff in their

mouths – and the food industry is supporting this behavior by advertising

their products as “high-protein” and "Atkins-approved" – as if this was somehow good for the

body. This paradox is age-old, and because it is ruled by emotions,

rather than clear thinking, a change in mind-set in your lifetime, should

not be expected.

Two thousand years ago, in this Bible passage, Paul

asked for tolerance between meat eaters and vegetarians (Romans 14:1-2).

“One man’s faith allows him to eat everything, but another man whose faith

is weak, eats only vegetables. The man who eats everything must not look

down on him who does not, and the man who does not eat everything must not

condemn the man who does...” Do not wait for a consensus before you take action.

References:

1) Chittenden, R. H. (1905).

Physiological economy in nutrition, with special reference to the

minimal protein requirement of the healthy man. An experimental study. New

York: Frederick A. Stokes Company.

2) Fire Retardant Treated Plywood:

http://www.nexsenpruet.com/library/docs/NPCOL1_624753_1.pdf

3) Calloway DH. Sweat and miscellaneous

nitrogen losses in human balance studies.

J Nutr. 1971 Jun;101(6):775-86.

4) Hegsted DM.. Minimum protein

requirements of adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1968 May; 21(5): 352-7.

5) Dole V. Dietary treatment of

hypertension: clinical and metabolic studies of patients on the rice-fruit

diet, J Clin Invest, 1950; 29: 1189-1206.

6) Millward DJ. The nutritional value of

plant-based diets in relation to human amino acid and protein

requirements. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999 May;58(2):249-60.

7) Mazess RB. Bone mineral content of

North Alaskan Eskimos. Am J Clin Nutr. 1974 Sep; 27(9): 916-25.

8) Brenner BM. Dietary protein intake and

the progressive nature of kidney disease: the role of hemodynamically

mediated glomerular injury in the pathogenesis of progressive glomerular

sclerosis in aging, renal ablation, and intrinsic renal disease. N Engl

J Med. 1982 Sep 9; 307(11): 652-9.

9) Meyer TW. Dietary protein intake and

progressive glomerular sclerosis: the role of capillary hypertension and

hyperperfusion in the progression of renal disease. Ann Intern Med.

1983 May; 98(5 Pt 2): 832-8.

10) Hansen HP. Effect of dietary protein

restriction on prognosis in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Kidney

Int. 2002 Jul; 62(1): 220-8.

11) Biesenbach G. Effect of mild dietary

protein restriction on urinary protein excretion in patients with renal

transplant fibrosis. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1996; 146(4): 75-8.

12) Pedrini MT. The effect of dietary

protein restriction on the progression of diabetic and nondiabetic renal

diseases: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1996 Apr

1;124(7):627-32.

13) Cupisti A. Vegetarian diet alternated

with conventional low-protein diet for patients with chronic renal

failure. J Ren Nutr. 2002 Jan;12(1):32-7.

14) Bianchi GP. Vegetable versus animal

protein diet in cirrhotic patients with chronic encephalopathy. A

randomized cross-over comparison. J Intern Med. 1993 May; 233(5): 385-92.

15) Abelow B.

Cross-cultural association between dietary animal protein and hip

fracture: a hypothesis. Calcific Tissue Int 50:14-8, 1992.

16) Frassetto LA .

Worldwide incidence of hip fracture in elderly women: relation to

consumption of animal and vegetable foods. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med

Sci. 2000 Oct;55(10):M585-92.

17) Maurer M.

Neutralization of Western diet inhibits bone resorption independently of K

intake and reduces cortisol secretion in humans. Am J Physiol Renal

Physiol. 2003 Jan;284(1):F32-40.

18) Remer T.

Influence of diet on acid-base balance. Semin Dial. 2000

Jul-Aug;13(4):221-6.

19) Frassetto L.

Diet, evolution and aging--the pathophysiologic effects of the

post-agricultural inversion of the potassium-to-sodium and

base-to-chloride ratios in the human diet. Eur J Nutr. 2001

Oct;40(5):200-13.

20) Remer T. Potential

renal acid load of foods and its influence on urine pH. J Am Diet

Assoc. 1995 Jul;95(7):791-7.

21) Barzel US. Excess dietary protein can

adversely affect bone. J Nutr. 1998 Jun;128(6):1051-3.

22) Maurer M. Neutralization of Western

diet inhibits bone resorption independently of K intake and reduces

cortisol secretion in humans. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003 Jan;

284(1): F32-40. Epub 2002 Sep 24.

23) Remer T. Potential

renal acid load of foods and its influence on urine pH. J Am Diet

Assoc. 1995 Jul;95(7):791-7.

24) J Pennington. Bowes & Church’s

Food Values of Portions Commonly Used. 17th Ed.

Lippincott. Philadelphia- New York. 1998.

25) Massey LK . Dietary animal and plant

protein and human bone health: a whole foods approach. J Nutr.

2003 Mar; 133(3): 862S-865S.

26) Jenkins DJ. Effect of high vegetable

protein diets on urinary calcium loss in middle-aged men and women.

Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003 Feb;57(2):376-82.

27) Lemann J Jr. Relationship between

urinary calcium and net acid excretion as determined by dietary protein

and potassium: a review. Nephron. 1999; 81 Suppl 1: 18-25.

28) Delvecchio FC. Medical management of

stone disease. Curr Opin Urol. 2003 May; 13(3): 229-33.

29) Remer T. Influence of diet on

acid-base balance. Semin Dial. 2000 Jul-Aug; 13(4): 221-6.

30) Troen AM. The atherogenic effect of

excess methionine intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Dec 9;

100(25): 15089-94.

31) Cellarier E. Methionine dependency

and cancer treatment. Cancer Treat Rev. 2003 Dec; 29(6): 489-99.

32) Epner DE. Nutrient intake and

nutritional indexes in adults with metastatic cancer on a phase I clinical

trial of dietary methionine restriction. Nutr Cancer. 2002; 42(2):

158-66.

33) Paulsen JE. Growth stimulation of

intestinal tumours in Apc(Min/+) mice by dietary L-methionine

supplementation. Anticancer Res. 2001 Sep-Oct; 21(5): 3281-4.

34) Stubbs AK. Nutrient-hormone

interaction in the ovine liver: methionine supply selectively modulates

growth hormone-induced IGF-I gene expression. J Endocrinol. 2002

Aug; 174(2): 335-41.

35) Yu H. Role of the insulin-like growth

factor family in cancer development and progression. J Natl Cancer

Inst. 2000 Sep 20;92(18):1472-89.

36) Levine J. Fecal hydrogen sulfide

production in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998

Jan;93(1):83-7.

37) Roediger W. Sulphide impairment of

substrate oxidation in rat colonocytes: a biochemical basis for ulcerative

colitis? Clin Sci (Lond). 1993 Nov;85(5):623-7.

38) Christl S. Effect of sodium sulfide

on cell proliferation of colonic mucosa. Gastroenterology 1994;

106:A664 (abstr).

39) Zimmerman JA.

Nutritional control of aging. Exp Gerontol. 2003 Jan-Feb; 38(1-2):

47-52.

40) McCay C. The effect

of retarded growth upon length of lifespan and upon ultimate body size.

J Nutr. 1935; 10: 63-79.

41) McDougall J.

Halitosis Is More than Bad Breath . McDougall Newsletter. January

2002 at

www.drmcdougall.com.

42) McDougall J. Bad

Farts? Meat Stinks! McDougall Newsletter. August 2002 at

www.drmcdougall.com.

|