|

Artificial Sweeteners Are

Unnecessary and Unwise

Life on earth for us begins with

breast milk, a food that is half sugar—and sugar in the

forms of simple and complex carbohydrates, found in

starches, vegetables, and fruits, ideally makes up the bulk

of our diet for the next 83 years (after weening). The food

industry is well aware of our inborn love affair with

sweet-taste. These profiteers lace our food supply with

concentrated and purified sugars, such as fructose and

sucrose (white table sugar)—totaling up to 158 pounds per

person annually. Along with the ever increasing popularity

of sugar, problems of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and

tooth decay have become more common in Western societies

over the past century. The belief that sugar plays the major

role in the fattening of people has led to the development of intensely sweet-tasting, lower- or no-calorie

substitutes. Up to 90% of people living in the USA now

consume beverages and foods containing sugar substitutes.

of intensely sweet-tasting, lower- or no-calorie

substitutes. Up to 90% of people living in the USA now

consume beverages and foods containing sugar substitutes.

Artificial sweeteners, as they

are commonly called, come in two general categories:

sugar alcohols which are on average 2 calories per gram

(compared to 4 calories per gram for purified sugars) and

nonnutritive sweeteners (at 0 calories/gram).

According to the American Dietetic Association,

“Nonnutritive sweeteners are safe for use within the

approved regulations. They can increase the palatability of

fruits, vegetables, and whole-grain breads/cereals and thus

have the potential to increase the nutrient density of the

diet while promoting lower energy intakes.”1 This

statement may be true if refined sugars are replaced, rather

than what people commonly do, which is to add artificial

sweeteners to their already sugar-laden diet.

| |

Sugar Substitutes

Sugar Alcohols

Sorbitol

Mannitol

Xylitol

Erythritol

Tagatose

Isomalt

Lactitol

Maltitol

Trehalose

HSH 3

Sugar alcohols are

incompletely absorbed from the gut; as a result,

they can cause a smaller rise in blood sugar,

decrease dental caries, and supply undigested sugars

to the bowel bacteria for their food, but they may

also lead to intestinal gas, cramps, and diarrhea.

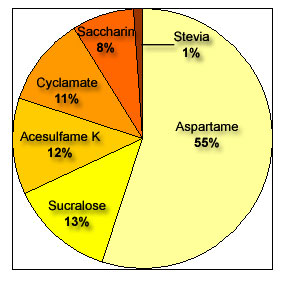

Nonnutritive

Sweeteners

From Forbes 2005

www.forbes.com/business/global/2005/0110/020.html

|

Saccharin:

|

|

|

Sweet ’N Low

Sweet Twin

Necta Sweet |

|

Aspartame: |

|

|

Nutrasweet

Equal

Sugar Twin |

|

Neotame: |

|

|

(Food

additive) |

|

Acesulfame-K: |

|

|

Sunett

Sweet & Safe

Sweet One |

|

Sucralose:

|

|

|

Splenda |

|

Additional nonnutritive sweeteners not now sold

in the USA

as sugar substitutes are: Alitame, Cyclamate,

Neohesperidine, Stevioside (Stevia), and

Thaumatin. |

|

No Substitute for Real Sugar

Sugar provides more sweetness—it

adds moisture, bulk, a lighter and fluffier texture to baked

goods, and it browns—artificial sweeteners don’t have these

cooking qualities. These manmade sweeteners are described

as being too sweet, having a chemical or bitter taste, and

having strong aftertastes—they also seem to block other

flavors of the foods they are used with. Since none of

these sweeteners provides the same clean taste, mouth-feel,

and cooking benefits as real sugar, new artificial

sweeteners continue to be developed—but so far not one has

become an acceptable sugar substitute for particular chefs

and consumers.

|

|

A Brief History of

Artificial Sweeteners

The first artificial

sweetener, saccharin, was synthesized in 1879. It

became popular because of its low cost of production

at the time of sugar shortages during World Wars I

and II. After these wars, when sugar once more

became available and inexpensive, the reasons for

using saccharin shifted from economics to health

(calorie reduction primarily). In the 1950s

cyclamate was introduced, and Sweet ’N Low became a

popular mixture of a blend of saccharin and

cyclamate. The artificial sweetener market was

shaken in the 1970s when the FDA (Food and Drug

Administration) banned cyclamate from all dietary

foods in the USA because of a cancer risk found in

experimental animals (other countries still allow

cyclamate). In 1981 the next artificial sweetener,

aspartame, marketed as Nutra-Sweet, became popular.

Since then several new nonnutritive sweeteners have

been introduced with a promise to be more like real

sugar with few calories. |

Artificial Sweeteners Help

Few Dieters

The benefit of artificial

sweeteners for weight loss is questioned for several

reasons. First, as stated in the position paper of the

American Dietetic Association, “Existing evidence does not

support the claim that diets high in nutritive sweeteners

(real sugars) by themselves have caused an increase

in obesity rates or other chronic conditions (e.g.

hyperlipidemia, diabetes, dental caries, behavioral

disorders).”1 Sugar appears to be, at most, a

minor player as the cause of obesity and related health

problems; therefore, replacement with an artificial sugar

would be expected to result in few benefits.

Other components of the diet

such as fats, oils, meats, and dairy products are the major

health burdens, not sugar. Think about the last time you saw

an obese person standing in line at the counter of your

favorite fast food restaurant. Did he/she order a diet

soda? Of course! If the act of ordering (always) that kind

of artificially sweetened drink made any real difference

then the customer would not have been so big. The soda is

the penance for the real sin—the supersized meal, washed

down by the diet soda.

Only a few studies have been

done to test the value of replacing sugar with artificial

sweeteners and they were done under highly controlled

experimental situations. Even then they show minimal

benefits—a long-term weight loss of only 6 to 10 pounds in a

year.2 However, controlled experiments do not

represent real life. Obesity throughout the world has

increased at the same time as has the consumption of

nonnutritive sweeteners—in part because most people simply

add these nonnutritive sweeteners without improving their

overall diet and lifestyle.

Sweeteners Cause Us to Eat

More

Benefits from the use of

artificial sweeteners are limited, in part, because they do

not deliver the same hunger-satisfying capacity as white

sugar. As a result, we are left seeking rewarding food—and

we follow our diet soda with our favorite candy bar (made of

the real thing). There is also some evidence that

artificial sweeteners can increase the appetite.3,4

Prolonged and intense gustatory

stimulation causes taste adaptation—a gradual decline

of taste intensity from the stimulation, whereby the taste

buds and the brain become less sensitive to the next dose of

sweet substance. In a short time, one 300 calorie

high-fructose corn syrup soda no longer provides us with a

decent “sugar high.” Now, in order to get equal pleasure,

two bottles of soda are required, then three… Because

artificial sweeteners are 200 to 13,000 times sweeter than

sugar their intense stimulation can quickly and profoundly

desensitize the mechanisms of appetite satisfaction.

Fourteen female students in one

recent study were fed three different beverages—water,

sugar-containing lemonade (an extra 330 extra calories) and

a similar lemonade made with aspartame—and their daily food

and calorie intake was measured.5 Regardless of

the beverage they drank on that day, they consumed the same

number of calories. The body adjusted—no harm was found

from the added sugar and no advantage was seen with the

no-calorie, aspartame sweetener. What was most revealing

was what happened the following day. After consuming the

lemonade with the aspartame, women ate significantly greater

amounts of energy (calories) compared to the day following

water or sugar-containing lemonade. The artificial

sweetener stimulated their appetite—and they ate more the

next day.

Do Artificial Sweeteners

Cause Health Problems?

Artificial sweeteners have been

accused of causing cancer, hair loss, depression, dementia,

headaches, autoimmune diseases, and behavioral

disturbances. However, the scientific consensus is that

they are acceptable in the diet and safe. (One notable

exception is for the use of aspartame for people with a rare

condition called phenylketonuria—PKU.) A level of

skepticism about their safety should be maintained because

there are a few people who do react adversely to these

chemicals, research on their safety is far from complete,

and financial vested interests have undoubtedly tainted the

truth. Furthermore, by combining many different sweeteners

in a food, manufacturers can assure their products do not

exceed potentially toxic levels of a single sweetener.

Whether or not these chemicals potentiate each other’s toxic

and cancer-causing effects has not been adequately studied.

Beginning in the 1970s, animal

studies found an excess of bladder cancer risk in rodents

treated with extremely high doses of saccharin. After three

and a half decades of research, the overall conclusion is

that the use of artificial sweeteners in very large amounts

(greater than 1.7 grams a day) is associated with a small

increased risk for bladder cancer in humans (relative risk

of 1.3).6,7 Daily intakes are on the order of

only a few milligrams for consumers. Newer sweeteners (acesulfame-K,

sucralose, alitame and neotame) have not been on the market

long enough to determine whether or not they cause more

cancer or other health problems.

Stevia—A Natural, Safe, and

Powerful Sweetener

From the leaves of a perennial

shrub found in Paraguay and Brazil comes a substance that is

200 to 300 times sweeter than table sugar. This stable

sweetener is essentially calorie-free, time-tested, and

non-toxic—and therefore may be the best choice if you must

use a sugar-substitute. Stevia, and its pure white active

ingredient, stevioside, are safe when used as a sweetener

and no allergic reactions to it have been reported.8

This natural sugar substitute has been used for centuries in

South America and Asia. The governments of Brazil, Korea,

and Japan approve of the use of Stevia leaves, and highly

purified extracts, as non-caloric sweeteners.8 From the leaves of a perennial

shrub found in Paraguay and Brazil comes a substance that is

200 to 300 times sweeter than table sugar. This stable

sweetener is essentially calorie-free, time-tested, and

non-toxic—and therefore may be the best choice if you must

use a sugar-substitute. Stevia, and its pure white active

ingredient, stevioside, are safe when used as a sweetener

and no allergic reactions to it have been reported.8

This natural sugar substitute has been used for centuries in

South America and Asia. The governments of Brazil, Korea,

and Japan approve of the use of Stevia leaves, and highly

purified extracts, as non-caloric sweeteners.8

Animal and human studies have

demonstrated anti-hypertensive and anti-diabetic properties

of Stevia.8-11

For example, in one

study patients took capsules containing 500 mg

stevioside powder or placebo 3 times daily for 2 years.

After 2 years, the stevioside group showed a decrease in

blood pressure from 150/95 mmHg to 140/89 mmHg compared with

placebo.9 In another study, 1 gram of stevioside

daily reduced blood sugar levels after eating by 18% in

type-2 diabetic patients.11

Stevia is cheap and easy to grow. This sweetener is used as

dried leaves, a white purified extract, and as a liquid. In

the US, Stevia is sold as a “dietary supplement,” rather

than as a replacement for sugar for legal reasons. Stevia is

not approved by the FDA, nor is it endorsed by the American

Dietetic Association as a nonnutritive sweetener. The lack

of official support has been attributed to pressures from

the sugar and artificial sweetener industries. The American

Dietetic Association receives their funding from many

industries, including those that manufacture artificial

sweeteners and foods made with these sugar-substitutes and

natural sugars.12

Substitute Good Food for

Artificial Taste

Sweet-tasting substances gratify

one of our most powerful and seductive desires. The

low-calorie sugar substitutes are supposed to offer an easy

way out—a means to partially circumvent damage to our teeth,

elevation of our blood fats (triglycerides), and fattening

our waistlines—and still allow us to enjoy the pleasures of

sweetness. However, these chemicals fall short on taste and

the promises for better health and weight loss. The right

way to deal with our innate desire for sugars is to get them

from whole foods—from starches, vegetables, and fruits.

One big problem with the Western

diet is it is deficient in healthy sugars—leaving us

wanting. People chew through platefuls of sugar

(carbohydrate)-deficient red meat, poultry, fish, and cheese

without becoming satisfied. Then at the end of the meal

they find a sugar-filled dessert—a calorie-bomb of

pleasure—in pie, ice cream, and cake. The reward is like a

fix to an addict.

Our love for sugar is inborn,

but it is adaptable—we can learn in a short time to enjoy

more flavorful foods with less intense sweetness—thus

eliminating our need to resort to artificial sweeteners.

Try this experiment: Eat for several days meals that provide

healthy sugars—those found on the McDougall Diet. My

experience, and the experience of others who have followed

the McDougall Diet, has been that after consuming a

plentiful supply of these sugars throughout the meal your

palate will be fully satisfied and those sugary desserts—the

ones you have felt addicted to—will lose their power over

you.

References:

1) American

Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic

Association: use of nutritive and nonnutritive sweeteners.

J Am Diet Assoc. 2004 Feb;104(2):255-75.

2) Vermunt

SH, Pasman WJ, Schaafsma G, Kardinaal AF. Effects of sugar

intake on body weight: a review. Obes Rev. 2003

May;4(2):91-9.

3) Tordoff

MG, Alleva AM. Oral stimulation with aspartame increases

hunger. Physiol Behav. 1990 Mar;47(3):555-9.

4) Rogers PJ,

Blundell JE. Separating the actions of sweetness and

calories: effects of saccharin and carbohydrates on hunger

and food intake in human subjects. Physiol Behav.

1989 Jun;45(6):1093-9.

5) Lavin JH,

French SJ, Read NW. The effect of sucrose- and

aspartame-sweetened drinks on energy intake, hunger and food

choice of female, moderately restrained eaters. Int J

Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997 Jan;21(1):37-42.

6) Weihrauch

MR, Diehl V. Artificial sweeteners--do they bear a

carcinogenic risk? Ann Oncol. 2004 Oct;15(10):1460-5.

7) Lean ME,

Hankey CR. Aspartame and its effects on health. BMJ.

2004 Oct 2;329(7469):755-6.

8) Geuns JM.

Stevioside. Phytochemistry. 2003 Nov;64(5):913-21

9) Hsieh MH,

Chan P, Sue YM, Liu JC, Liang TH, Huang TY, Tomlinson B,

Chow MS, Kao PF, Chen YJ Efficacy and tolerability of oral

stevioside in patients with mild essential hypertension: a

two-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther.

2003 Nov;25(11):2797-808.

10) Chan P,

Tomlinson B, Chen YJ, Liu JC, Hsieh MH, Cheng JT. A

double-blind placebo-controlled study of the effectiveness

and tolerability of oral stevioside in human hypertension.

Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000 Sep;50(3):215-20.

11)

Gregersen S, Jeppesen PB, Holst JJ, Hermansen K.

Antihyperglycemic effects of stevioside in type 2 diabetic

subjects. Metabolism. 2004 Jan;53(1):73-6.

12) http://www.cspinet.org/integrity/nonprofits/american_dietetic_association.html |